Powder bagging rarely fails at the scale. It fails when the powder behaves unpredictably. Weight drift creeps in, dust escapes around the neck, and operators start tapping the chute to keep the flow moving. Bags fill smoothly one moment, then stall the next. Production slows, and no one is sure why.

Does your plant constantly wipe dust around the fill neck? That is not a cleaning issue. It is a sealing and airflow problem.

Choosing the right powder bagging machine is not about catalog size or throughput claims. It starts with how your powder actually moves through the hopper, how the fill head seals, and how the weighing system reacts to material instability. One wrong design choice can turn a stable cycle into a manual firefight.

This guide explains what matters, how to evaluate key components, and where a specialist manufacturer fits when standard machines cannot keep up.

Before You Choose a Powder Bagging Machine

Powder behavior decides everything. If the machine is not engineered around how your powder actually flows, it will force operators to compensate.

Geometry is a control tool, not a cosmetic choice. Hopper taper, sealing pressure, and venting determine whether flow stays stable or turns into dust plumes and surges.

Accuracy is won or lost in the final seconds of fill. The last phase of weighing is where overshoot, collapse, and drift show up if the system cannot slow down and stabilize.

Operator habits are symptoms, not solutions. Tapping, shaking, or repositioning bags indicates poor design alignment with your powder, not “operator training issues.”

Catalog machines are starting points, not endpoints. When humidity, abrasiveness, coating, or reclaim batches enter the equation, only engineered systems built around your material stay predictable.

Understand the Material That Runs Through Your Powder Bagging Machine

Powders do not behave like pellets or granules, and their movement changes with humidity, vibration, particle shape, and surface chemistry. When you select a powder bagging machine by bag size or price, you ignore the flow physics that control performance.

Cohesive powders need different fill heads and venting than free-flowing material, hygroscopic powders need sealed paths and stable inflation, and abrasive powders require reinforced surfaces. If the machine cannot handle these differences, you will see bridging, surging, or caking long before the scale can correct anything.

Material types and technical consequences you should consider:

Fill head sealing: Weak sealing increases air turbulence and causes dust plumes

Hopper taper: Too shallow creates hang-ups, too steep accelerates uncontrolled flow.

Vibration intensity: Over-vibration fluidizes powders and reduces accuracy.

Feed rate: Unstable feed forces operators to tap or shake the system.

When you match material behavior to machine geometry, you prevent operator intervention and stabilize your bagging cycle.

Powder Flow Categories and Their Impact on Machine Design

You are not choosing a machine. You are choosing a flow strategy. Mis-matching a system to the material class forces your operators to compensate, and that is the first sign that the design is wrong. Understanding the category your powder belongs to will help you set the right bagging conditions.

Below are the four major powder categories and the engineering responses they demand:

Cohesive powders

Behavior: form bridges and compact under their own weight.

Required design: anti-bridging plates, steeper hopper taper, controlled low-intensity vibration, slow initial feed start to prevent arching.

Free-flowing powders

Behavior: surge and accelerate uncontrollably once motion begins.

Required design: steady feed rate, dual-stage cutoff for final weight accuracy, stable fill neck sealing to avoid blowback, minimal excess vibration.

Hygroscopic powders

Behavior: absorb moisture, form crust, and shift density during filling.

Required design: sealed fill path, stable inflation pressure, moisture-controlled hopper, short dosing cycles to prevent buildup, smooth internal surfaces to avoid film formation.

Abrasive powders

Behavior: wear down valves, screws, and contact surfaces.

Required design: hardened or sacrificial components, protected internals, low-friction linings, indirect feed systems that reduce particle-to-metal abrasion.

Use this table to cross-check material type against the most critical machine features:

Powder Type | Primary Risk | Key Design Focus | Signs of Mismatch |

Cohesive | Bridging and compaction | Anti-bridging plates, hopper taper, controlled vibration | Operators tapping, inconsistent start of flow |

Free-flowing | Surging and overshoot | Feed rate stability, dual-stage cutoff, and sealing | Weight overshoot, dust burst at fill head |

Hygroscopic | Moisture absorption | Sealed path, inflation stability, surface finish | Caked residue, slow refill cycles |

Abrasive | Wear on internals | Hardened parts, protected feed components | Frequent maintenance, valve degradation |

When you classify the powder correctly, you control the flow before it becomes an accuracy issue. That is the difference between a line that runs on schedule and one where operators constantly intervene.

The 5A from H&H Design & Manufacturing gives you clean, predictable fills for free-flowing materials like grains and pellets. If you need a gravity-fed system that runs steady without operator tapping, this is where you start.

When you understand how your powder behaves, the next question is simple: can the machine’s hardware actually manage it consistently? This is where the core components decide whether your bagging line runs calmly or becomes a constant rescue mission.

Core Components That Define a Powder Bagging Machine

Not all powder bagging machines are equal, and performance depends on how each system manages powder flow, containment, and weighing accuracy. What matters in real plant conditions is the hopper geometry, the fill neck and sealing assembly, and the weighing strategy. If a machine cannot control flow or seal the bag properly, it quickly becomes a cycle of cleanup, scale resets, and operator intervention.

Key engineering elements to evaluate:

Hopper geometry: Taper angle controls discharge stability. Smooth interior surfaces prevent friction stalls. Anti-bridging features keep powder moving instead of arching.

Fill neck and sealing: Correct pressure and clamping contain dust. Inflation stabilizes bag volume. Proper venting prevents blowback and turbulence.

Weighing strategy: Gross or net weighing determines how mass is measured. The last 3 percent of the cycle defines whether the system hits tolerance or misses it.

Hopper and Feed System Requirements for Powder Stability

The hopper is the start of every failure mode. If powder collapses, surges, or compacts here, nothing downstream will run consistently. A stable discharge path prevents operators from tapping or shaking equipment to restart flow.

Different feed methods suit different powder behaviors and throughput goals:

Gravity feed: Works for stable, low-friction powders that flow without resistance. Requires proper hopper taper and smooth surfaces to avoid sudden acceleration.

Screw feed: Best for cohesive powders that resist movement. The screw meter controls volume, reduces bridging, and provides a steady feed for weighing.

Vibratory feed: Useful for powders that fluidize under motion. Light vibration helps maintain a thin, controlled stream and prevents caking.

Dual-stage feed: Ideal when you need high throughput with high accuracy. The first stage fills to near the target. The second stage uses a slower, finer stream to prevent overshoot.

Example of real engineering outcomes:

A cohesive mineral powder in a shallow hopper forms arches. Operators hit the hopper to restart the flow. A steep taper with anti-bridging inserts removes the intervention.

A free-flowing sugar powder surges during gravity feed. It overshoots the target weight. Switching to dual-stage feed stops the surge and stabilizes the final fill.

Weighing and Bag Inflation Control in Powder Bagging Machines

Scale sensitivity is not the root of inconsistent fills. Instability starts when the powder enters the bag. Inflation keeps the bag open, forms the internal cavity, and gives the scale consistent resistance. Without it, powder hits folds, collapses volume, and produces rebound errors.

Two weighing methods and where each fits:

Gross weighing: Measures the bag and product together. Acceptable for simple installations or lower throughput. Less control during the final fill stage.

Net weighing: Measures only the product. Better for powders that surge or compact. The scale reacts faster and adjusts before overshoot.

Inflation and support variables that matter:

Inflation pressure: Too low, collapses the bag during early fill. Too high amplifies dust leakage and unstable flow.

Bag support: Side supports, neck clamps, and base platforms stop sagging and reduce weight drift.

Settling cycles: Controlled vibration settles material between feed stages. Short bursts prevent fluidization and powder suspension.

Single-stage vs double-stage fill guidance:

Single-stage: Appropriate when density is consistent and flow is predictable. The bag fills continuously until the target is reached.

Double-stage: Necessary for powders that surge or fluidize. The first stage fills fast. The second stage slows the feed for tight tolerance.

You can tame the flow and stabilize the scale, but the job is not done if the powder escapes the bag. Once it enters the air, safety and dust control take over the conversation.

Safety, Dust Control, and Operator Consequences in a Powder Bagging Machine

Dust is not cosmetic. It is a compliance hazard, an exposure risk, and an ongoing cost that shows up as filter waste, cleanup hours, and slow production.

Dust escapes when sealing at the neck ring fails. Weak clamping pressure or poorly timed inflation allows powder to follow escaping air. Airflow at the wrong moment carries particles out of the bag and into the surrounding space, which increases filter load and maintenance downtime.

How sealing and containment should perform:

Neck clamping must form a uniform seal that stays stable during fill acceleration and final cutoff.

Inflation timing must create a cavity before powder enters, or material hits folds and rebounds.

Vent channels must be sized to match fill rate, not simply added as an accessory.

You typically choose between passive and active dust collection:

Active dust collection pulls air through a controlled suction path. Suitable for fine powders that disperse easily. Must match the fill rate or turbulence forms at the fill neck.

Passive dust collection uses sealed fill paths, pressure relief, and staged venting. Works with powders that settle quickly and generate less airborne fines.

When operators tap hoppers, shake bags, or adjust position during a cycle, you are observing system mis-sizing. These behaviors are compensation for unstable flow, not performance issues with the workforce.

The 330E from H&H Design & Manufacturing is a bulk bag filler built for high-throughput operations that need clean, consistent performance with automation. If your plant targets 20–30 bags per hour and wants fewer operator touches, this system delivers steady fills at industrial scale.

If dust control keeps the room clean, throughput keeps the line honest. Now the question is how many bags you can fill accurately without constant intervention.

Matching a Powder Bagging Machine to Throughput and Bag Type

Throughput is not how many bags per hour you can run on paper. It is how often the machine fills to tolerance without manual fixes.

Bag size, fill speed, particle density, and vibration cycles determine true output. A small bag with a dense powder may hit the target faster but overshoot more easily. A large bag may require a slower final feed and longer settling. Too much vibration fluidizes material, too little causes inconsistent packing.

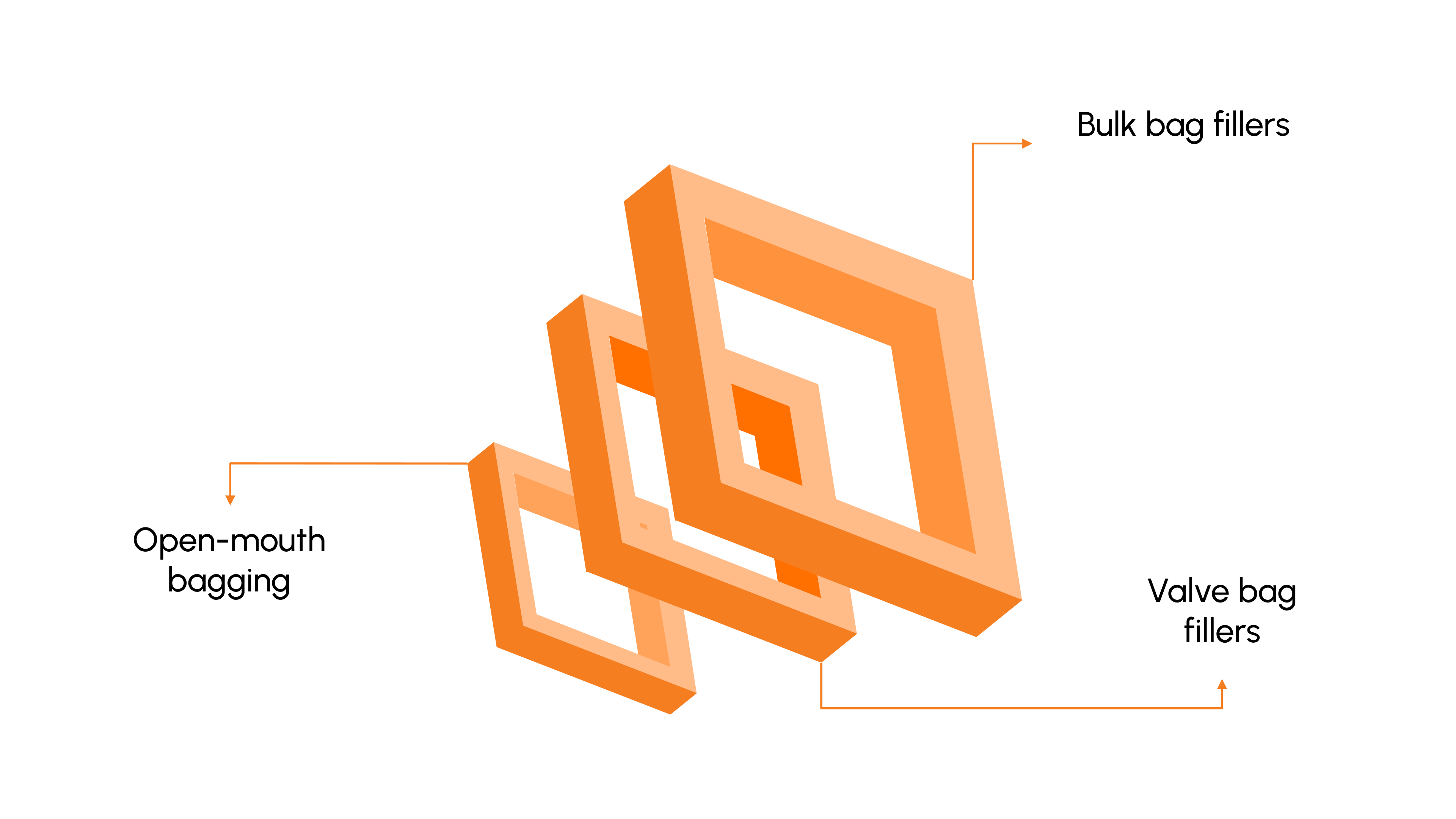

Bagging formats and where they make sense:

Bulk bag fillers: Suitable for large units where accurate weight and inflation stability prevent collapse and dust bursts.

Valve bag fillers: Restrict material at the inlet, useful for powder with high dust potential or unstable discharge.

Open-mouth bagging: Works for stable powders or coarse blends. Requires strong sealing and airflow control to avoid dust migration.

Choosing machines by nominal capacity leads to inflated expectations. A system that technically runs one hundred bags per hour but consistently misses tolerance is less productive than a system that hits a target at eighty.

When throughput falls apart even with the right bag type, it is not speed. It is a sign that a standard machine is no longer enough.

When a Standard Powder Bagging Machine Is Not Enough

A catalog machine works only when the material behaves as expected. If the powder cakes, surges, or wears equipment, the operator becomes the safety valve.

Custom design is triggered by specific conditions:

Coated or electrostatic powders that stick to surfaces.

Highly abrasive powders that erode valves, screws, and neck rings.

Hygroscopic or humidity-sensitive materials that change density mid-cycle.

Restricted plant layouts that force poor hopper angles and discharge geometry.

Replacing individual parts treats symptoms. Designing around powder flow prevents them. A system built for your material runs clean, fills predictably, and stops the cycle of taps, resets, and rework.

The 110DS-P from H&H Design & Manufacturing is a bulk bag filler designed for clean filling environments where dust must stay contained. If you run 100–4,400 lb bags and need 10–25 bags per hour without constant cleanup, this system keeps the process controlled and predictable.

When a standard machine hits its limit, the answer is not another quick fix. It is a partner who designs around your powder.

Why H&H Design & Manufacturing Matters for Powder Bagging Machines

At H&H Design & Manufacturing, we engineer powder bagging machines around your material, not a catalog sheet. We control design, fabrication, commissioning, and support, so the same team is responsible for performance over the machine’s life.

Cohesive powders get different tapers and augers, hygroscopic powders get sealed paths, and abrasive materials get reinforced internals. Because we build and install the equipment ourselves, we can adapt quickly when your powder or throughput changes.

What this approach gives you:

Custom configuration instead of one-size-fits-all layouts

Fast modifications when your product line changes

Direct interaction with engineers who understand failure modes

Support for legacy Tech Packaging Group equipment already in service

Below are examples of the systems we design and support.

Small Bag Filling Equipment

Series | Feed Method | Bag Type | Best For |

Gravity | Open Mouth | Free-flowing materials such as grains and pellets | |

Gravity | Open Mouth | Entry-level electronic gross weight for granules | |

Single auger | Open Mouth | Fine powders needing dust control and consistent rate | |

Dual auger | Open Mouth | Faster powder filling with a fine feed finish |

Bulk Filling Equipment

Series | Capacity | Bagging Rate | Ideal Use |

100–4,400 lb | 10–25 bags/hr | Adjustable frame for multiple bag sizes and materials | |

100–4,400 lb | 10–25 bags/hr | Clean filling environments where dust must stay contained | |

100–4,400 lb | 20–30 bags/hr | High-throughput operations with automation | |

Up to ~4,400–6,000 lb | High volume | Continuous-duty industrial plants and heavy materials |

These units are built for the challenges you face in real plants. Adjustable frames reduce downtime when switching bag sizes, and reinforced structures withstand dense or abrasive powders without constant repairs.

Conclusion

Choosing the right powder bagging machine is not about brochure capacity. It is about how the system handles material behavior, hopper geometry, weighing strategy, dust control, and stable throughput. Look at your plant honestly. If you see bag collapse, weight drift, operator tapping, or constant dust wiping, the equipment is not matched to your powder.

Connect with H&H Design & Manufacturing. We design powder bagging machines that run steady, stay clean, and make production days easier.

FAQs

Q: How often should a powder bagging machine be recalibrated in an active production environment?

A: Calibration intervals depend on duty hours and powder density changes. High-use lines benefit from weekly verification because density drift affects readings. Plants with consistent material can extend intervals but should schedule calibration after any maintenance or equipment change.

Q: What signs show that operators are overcompensating instead of the machine doing its job?

A: Manual scooping, nudging the feed path, or adding extra vibration are red flags of a design mismatch. If workers create shortcuts to keep bags moving, review the system sizing before blaming training.

Q: Can you run multiple powder SKUs on the same bagging line without redesigning the system?

A: Yes, if the core design includes adjustable flow paths and modular feed components. Systems with fixed geometry struggle when switching between powders, even if bag size stays the same.

Q: How does particle shape influence the way powder moves through a bagging system?

A: Irregular particles interlock and resist flow, while spherical particles accelerate and overshoot. Shape variability produces unstable feed rates, so metering must be tuned to particle form, not just density.

Q: What environmental factors have the biggest impact on day-to-day bagging performance?

A: Temperature and humidity shift powder moisture content, which changes compaction and flow. Static buildup is another hidden factor that shows up as sticking, coating, or delayed settling.

Q: Should operators adjust vibration settings during production, or should these be fixed?

A: Vibration intensity should not be changed mid-shift unless a documented procedure exists. Frequent adjustments signal that the baseline setup is wrong, not that operators need to “feel” the machine.